Sometimes things come together, strangely but appropriately.

Sometimes things come together, strangely but appropriately.

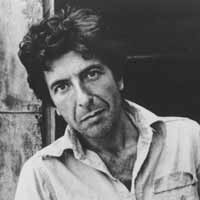

The news of Leonard Cohen’s death filtered through just as we heard that Donald Trump would be the next US President and just as ordinary Indians thronged the streets outside ATMs and bank branches, hoping desperately to withdraw the cash they needed to meet their daily needs. Outwardly, we were all optimistic but inwardly, we knew that there were more disappointments on the road ahead.

Everyone coped in different ways. I listened to Leonard Cohen. And to one song, in particular. It’s called Everybody Knows:

“Everybody knows that the dice are loaded

Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed.

Everybody knows that the war is over.

Everybody knows that the good guys lost

Everybody knows that the fight was fixed.

The poor stay poor, the rich stay rich.”

Finally I tweeted a few lines, because they seemed to me to capture the mood of our times. Obviously some people agreed; the tweet got around 300 likes.

But it was only one of thousands of tweets from around the world that quoted from Cohen’s songs in the aftermath of his death. A particular favourite were the words to Anthem. “There is a crack in everything/that’s how the light gets in.”

It was funny, I thought, how the world went back to quoting the elderly (or now dead) icons of the rock world, referencing songs they had written decades ago because they seemed to best fit today’s times. When Bob Dylan won his Nobel Prize, I wrote about the way in which his lyrics seemed eerily prescient. (“Even the President of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked”. That’s from Alright Ma, which Dylan wrote in 1965 and now seems truly scary when you have to think of Donald Trump that way.)

But Leonard Cohen, while never as great an influence or artiste as Dylan, differed substantially from many of his contemporaries. Last week, at the Lit Live Festival in Bombay, I spent a morning with Sam Cutler, the legendary rock manager from the 60s and 70s. (Sam was the MC at Altamont on that fateful night when his clothes were splattered with the blood of Meredith Hunter, the black man whom the Hell’s Angels killed at a Rolling Stones concert).

We discussed whether rock was a young man’s game. Sam had worked with Pink Floyd but was hard pressed to think of a great Floyd song from after the early 80s. (“Shine On You Crazy Diamond”, may have been their last hurrah.) Even the Stones, Sam’s claim to fame (he coined the phrase “the greatest rock and roll band in the world” to introduce them), have not written a great song for 30 years. I grieved for David Bowie some months ago but as for the music, it was pretty much downhill after Let’s Dance (1983). When you listen to Paul McCartney in concert these days you realise how rubbish the new stuff is. Even my own hero, Paul Simon, is unable to match the glories of his past.

In that sense, rock is different from other kinds of music. Does anybody care about how old the great jazz musicians were when they recorded their best stuff? The legendary blues singers were never young and the suffering was etched on their faces. The writers of standards (the Gershwins, Cole Porter, etc) transcended age. And so, I guess, does Hindi film music. When RD Burman composed the music for 1942, A Love Story, he was at the height of his powers, even though it was among the last scores he composed.

The exception to this whole rock-is-a-young-man’s-thing rule was, of course, Leonard Cohen, both Sam and I agreed. But that may have been because Cohen was, always different.

He was a well-known Canadian poet who was drawn into the world of music and encouraged to record his songs (like nearly everybody else in that era) by the success of Bob Dylan who proved you didn’t need to sing like an angel if the words were any good.

| "So yes, rock is a young man’s game. But Leonard Cohen beat that generalisation because he was never a rock star." |

His first album (Songs of Leonard Cohen) came out in 1968 and included the songs (Suzanne, Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye, So Long, Marianne, etc) that came to define him to a generation of listeners who listened to music for meaning. (Is there anyone in that generation who has not broken up to “Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye”?)

The following year, Cohen released Songs From A Room which pretty much completed his legend and included the other songs that would become famous (Bird on a Wire, Story of Isaac, The Partisan etc.)

So by 1969, he had already released the songs that a whole generation would remember him by. New albums followed but none had the same impact, though there were a handful of good songs through the 70s (Famous Blue Raincoat in 1971, and Who By Fire and Chelsea Hotel in 1974).

The 1980s, were a fallow decade and even the great songs went largely unnoticed. Nobody was very excited by Dance Me To The End of Love or Hallelujah (1985) or First We Take Manhattan, Everybody Knows or Tower of Song (1988) when they first appeared. The Suzanne generation had simply moved on.

So why do we remember Cohen today? Because of other singers, oddly enough.

Even after Cohen had been written off by his old fans and the music business, singers who had grown up on his songs, perhaps because their parents liked them, wanted to perform them.

In 1994, Jeff Buckley recorded Hallelujah as a stark, stripped-down cry of pain (his version was far superior to the original) and the Buckley song was a hit with a new generation that had never heard of Cohen. Hallelujah became a staple of talent shows: Janice Castro’s version from American Idol was a US number one in 2008; another version from The X-Factor was a British number one the same year. All this brought attention to the song.

By then Cohen’s life had undergone a massive change. Confident that he had now made more money than he would ever need, he retired from the music business and turned spiritual. He spent days at a snowbound retreat called Mount Baldy (the name sounds like the title of a Cohen song) and followed a Zen master called Roshi. Then, he discovered an Indian spiritual teacher called Ramesh Balsekar who was based in Bombay’s Warden Road. He was so taken with Balsekar that he spent several months in Bombay at a small hotel in Kemp’s Corner, listening to Balsekar. He would often walk down Warden Road, was rarely recognised and drew no attention to himself. (There is a terrific account of Cohen’s time in Bombay by someone who knew him during this phase on Scroll.in.)

The Leonard Cohen who had written Suzanne was gone. A new monk-like figure had taken his place.

Then, two things happened. One: his manager stole all his money, making profitable use of Cohen’s disappearance into spiritual retreats. And two: all of Cohen’s songs became famous again because of other versions. It wasn’t just Hallelujah but it was also songs like Everybody Knows which was used in movie soundtracks and widely covered (by Bob Dylan even!).

Cohen did what he had to, if he was to make a living again. He returned to the stage, performing a series of concerts and began writing new songs for new studio albums. It is wrong to feel some satisfaction at another man’s misfortune but I have to say, that from my unspiritual perspective, I’m glad the crooked manager forced Cohen back into the music.

I’ve seen the videos of his comeback gigs and heard the albums and they are mostly brilliant. I only saw him live once but it still remains one of the finest concerts I’ve seen. The old onstage Cohen was essentially a folk singer with a bad singing voice. But the later Cohen was a dapper old man in a smart suit and hat with a kick-ass band, and two great backing singers (the Webb sisters). Performing again after two decades, he showed us that his songs had aged like the best single malts: rich, smokey and full of unexpected notes.

More significantly, the new concerts were the places where the two generations of Cohen fans who knew two different sets of songs (the Suzanne generation and the Hallelujah generation) sat in the same row and realised that we were listening to a great master whose music had lasted over four decades and who was still at the top of his game.

So yes, rock is a young man’s game. But Leonard Cohen beat that generalisation because he was never a rock star. His words and his music defied classification. And even as I mourn him, I know the songs will live on. Because, as he told us himself, “There is a blaze of light in every word”.

Hallelujah!

Name:

Please enter name

E-mail:

Your email id will not be published.

Please enter email

Please enter a valid email address eg. xyz@abc.com !

Friend's Name:

Please enter friend name

Friend's E-mail:

Your email id will not be published.

Please enter friend email

Please enter a valid email address eg. xyz@abc.com !

Additional Text:

Security code:

Other Articles

Other Articles

-

Only five years ago I would have been stuck with Akasaka in Def Col. or Moti Mahal Deluxe in South Ex. Now I have amazing options to choose from.

-

In the pursuit of vegetarianism and vegetarian guests lies the future. And great profit.

-

I think that Indians have less desire to ‘belong’ than Brits do. We don’t need social approval. And this is a good thing.

-

And ask yourself: have I really been enjoying the taste of vodka all these years or just enjoyed the alcoholic kick it gives my cocktails?

-

There is a growing curiosity about modern Asian food, more young people are baking and the principles of European cuisine are finally being understood

See All